Benjamin

I am currently working on:

- 🗺️ Exploration Geophysics

- ☢️ Molecular Dynamics Simulation

- 🌍 Earth System Physics

Image credit: Shutterstock.

Exploration Geophysics

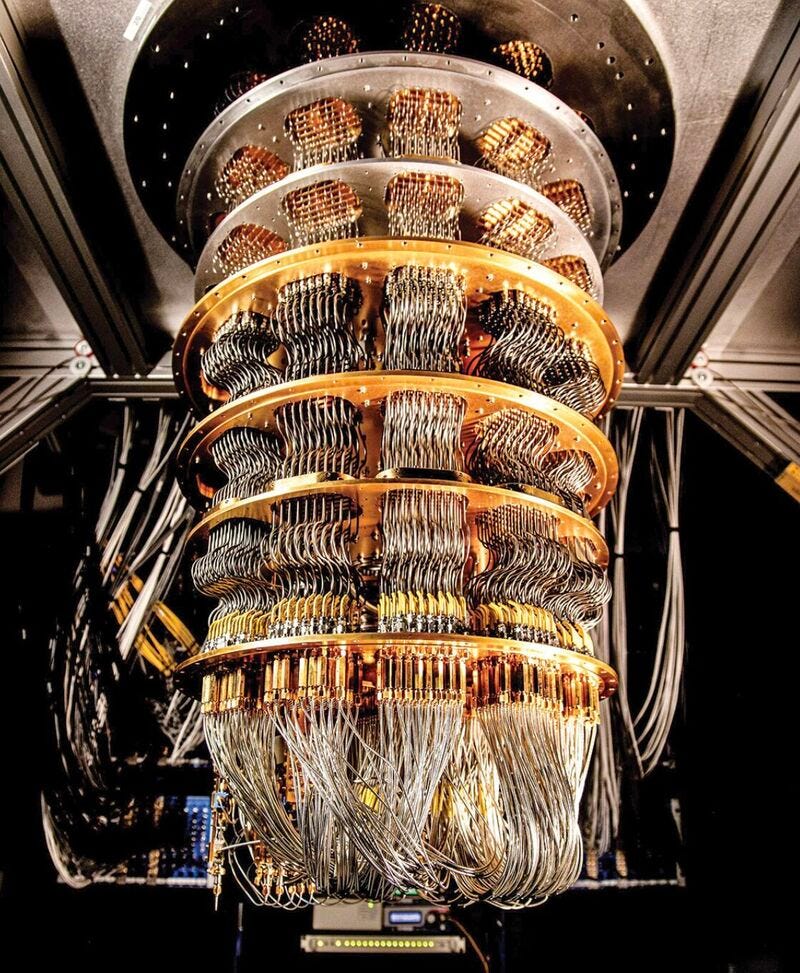

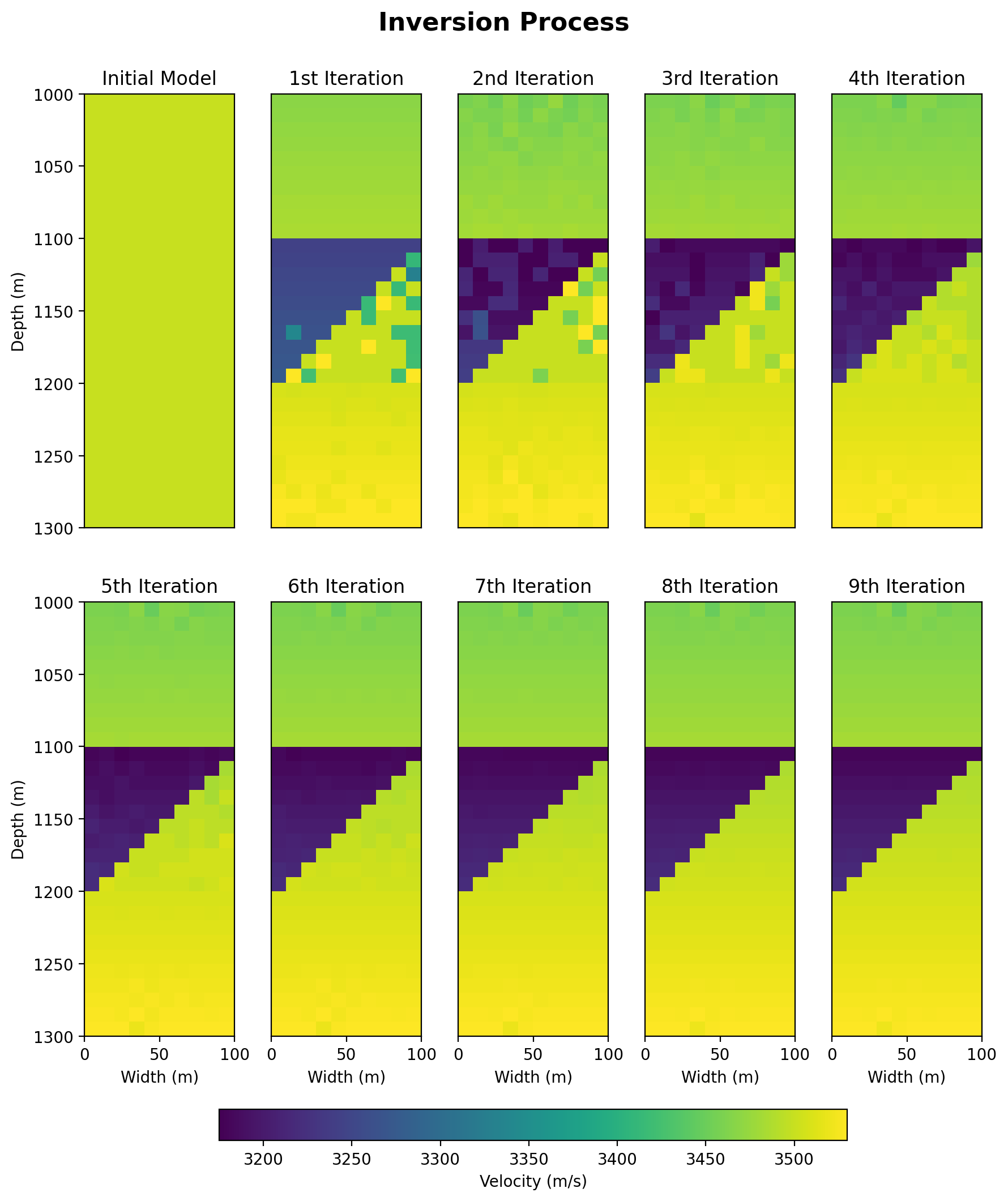

The seismic inversion with quantum computer system. Here I employ the computation via the open-access D-Wave Advantage system quantum annealer.

Quantum computing holds significant promise for revolutionizing seismic inversion, a key technique in geophysics used to infer subsurface properties from seismic data. Traditional seismic inversion methods involve solving large, complex optimization problems, which require processing vast amounts of data and running computationally intensive simulations. These tasks are often time-consuming and require significant computational resources. Quantum computing, with its ability to process and analyze information at unprecedented speeds, offers a potential breakthrough in tackling these challenges more efficiently, enabling faster and more accurate seismic inversion.

Image credit: Medium.

In seismic inversion, the goal is to create models of the Earth’s subsurface that best fit the observed seismic data. This typically involves iteratively adjusting the model parameters and running forward simulations to minimize the difference between the observed and synthetic data. Quantum computing could accelerate this process by exploiting quantum parallelism, which allows simultaneous exploration of multiple solutions in a much shorter time frame than classical computers. Quantum algorithms, such as quantum annealing and quantum machine learning, could significantly enhance the efficiency of searching for the optimal subsurface model, reducing the computational time from days or weeks to potentially hours or even minutes.

The integration of quantum computing into seismic inversion is still in its early stages, with ongoing research and development needed to fully realize its potential. Challenges such as developing suitable quantum algorithms and dealing with noise and error correction in quantum systems remain. However, as quantum technology continues to advance, it is expected to bring transformative changes to seismic inversion, enabling geophysicists to solve more complex problems, achieve higher-resolution subsurface images, and make more accurate predictions in fields such as oil and gas exploration, earthquake hazard assessment, and environmental monitoring.

Molecular Dynamics Simulation

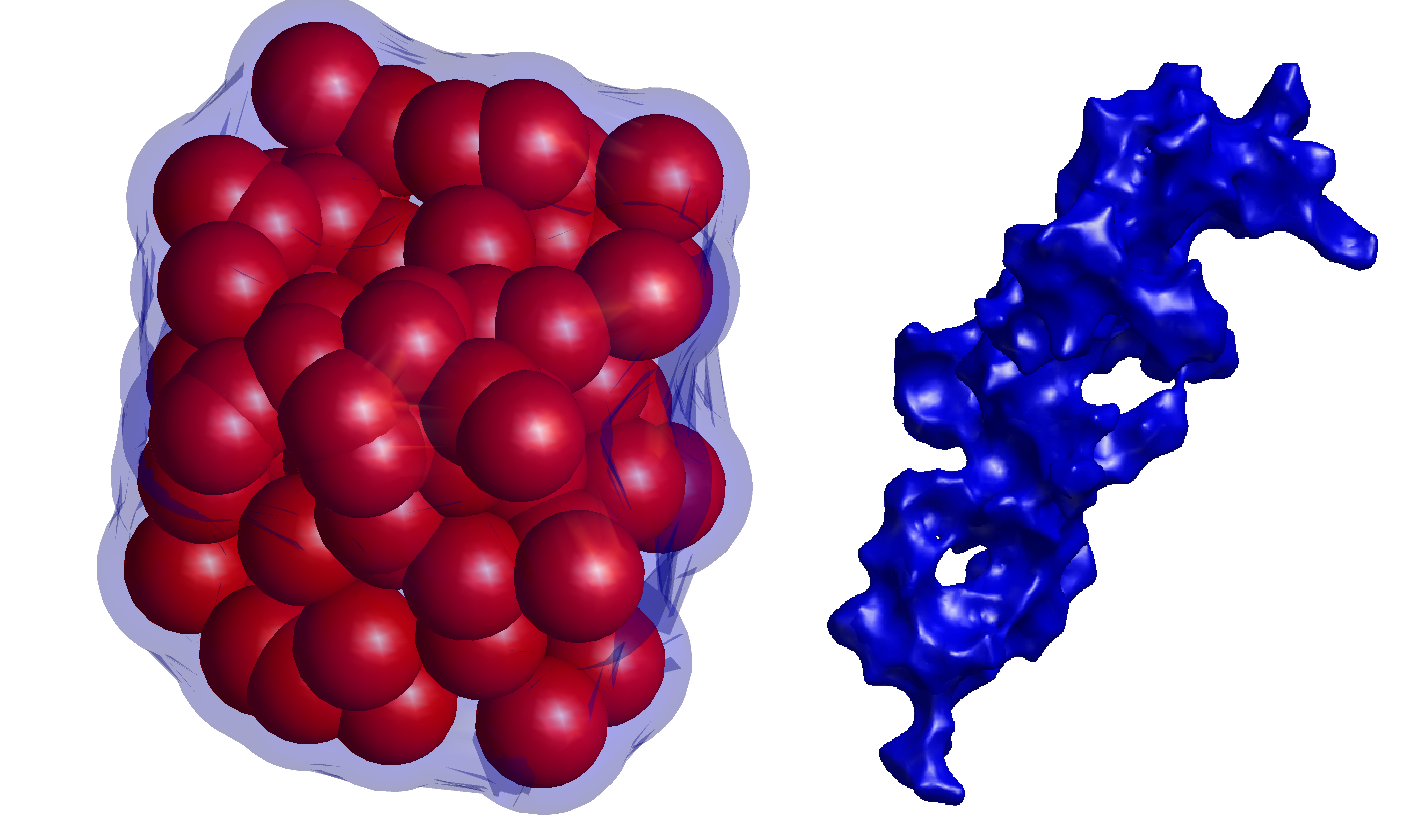

The image depicts a pore structure characterized by a cluster of red spheres and a surrounding blue shape. The red spheres represent the individual particles or void spaces within the pore, calculated using the DBSCAN (Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise) method. This clustering algorithm identifies and groups points (in this case, the voids) that are closely packed, allowing for the identification of the pore structure within the material.

The image depicts a pore structure characterized by a cluster of red spheres and a surrounding blue shape. The red spheres represent the individual particles or void spaces within the pore, calculated using the DBSCAN (Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise) method. This clustering algorithm identifies and groups points (in this case, the voids) that are closely packed, allowing for the identification of the pore structure within the material.

On the right, the blue shape represents the overall morphology of the pore, highlighting its irregular, interconnected nature. This blue contour provides a visualization of the pore’s boundary, enclosing the red spheres and indicating the extent and complexity of the pore’s shape.

This combined visualization of the red spheres and blue contour allows for a comprehensive understanding of both the internal distribution of void spaces and the overall pore structure within the material.

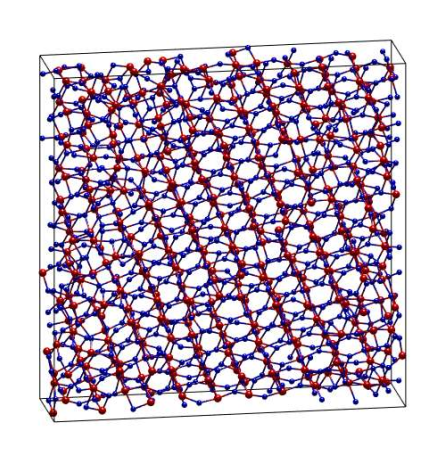

Crystallization of materials under high compression, particularly up to pressures as extreme as 100 GPa, is a topic of significant interest in the study of geophysics and material science. When subjected to such intense pressures, materials like SiO2 (silicon dioxide) undergo profound structural changes. At ambient conditions, SiO2 typically exists in the crystalline form of quartz, but as pressure increases, it transitions through several high-pressure polymorphs such as coesite and stishovite. These transformations involve the rearrangement of the silicon and oxygen atoms into denser configurations, which are more stable under high pressure. The study of these phase transitions is crucial for understanding the behavior of Earth’s mantle, where pressures can reach such extremes, and provides insight into the processes that govern the formation of planetary interiors. At pressures approaching 100 GPa, SiO2 may crystallize into even more complex structures, such as those similar to seifertite or other high-pressure phases that are not commonly found at the Earth’s surface. These high-pressure forms of SiO2 have different physical properties, including density and elastic moduli, which can significantly influence the mechanical behavior of materials in the deep Earth. Understanding the crystallization process under such conditions requires advanced experimental techniques, such as diamond anvil cells, as well as computational simulations to model atomic interactions at these extreme environments. Research in this area not only helps in reconstructing the conditions of Earth’s deep interior but also contributes to the development of materials that can withstand extreme pressures for technological applications.

Crystallization of materials under high compression, particularly up to pressures as extreme as 100 GPa, is a topic of significant interest in the study of geophysics and material science. When subjected to such intense pressures, materials like SiO2 (silicon dioxide) undergo profound structural changes. At ambient conditions, SiO2 typically exists in the crystalline form of quartz, but as pressure increases, it transitions through several high-pressure polymorphs such as coesite and stishovite. These transformations involve the rearrangement of the silicon and oxygen atoms into denser configurations, which are more stable under high pressure. The study of these phase transitions is crucial for understanding the behavior of Earth’s mantle, where pressures can reach such extremes, and provides insight into the processes that govern the formation of planetary interiors. At pressures approaching 100 GPa, SiO2 may crystallize into even more complex structures, such as those similar to seifertite or other high-pressure phases that are not commonly found at the Earth’s surface. These high-pressure forms of SiO2 have different physical properties, including density and elastic moduli, which can significantly influence the mechanical behavior of materials in the deep Earth. Understanding the crystallization process under such conditions requires advanced experimental techniques, such as diamond anvil cells, as well as computational simulations to model atomic interactions at these extreme environments. Research in this area not only helps in reconstructing the conditions of Earth’s deep interior but also contributes to the development of materials that can withstand extreme pressures for technological applications.

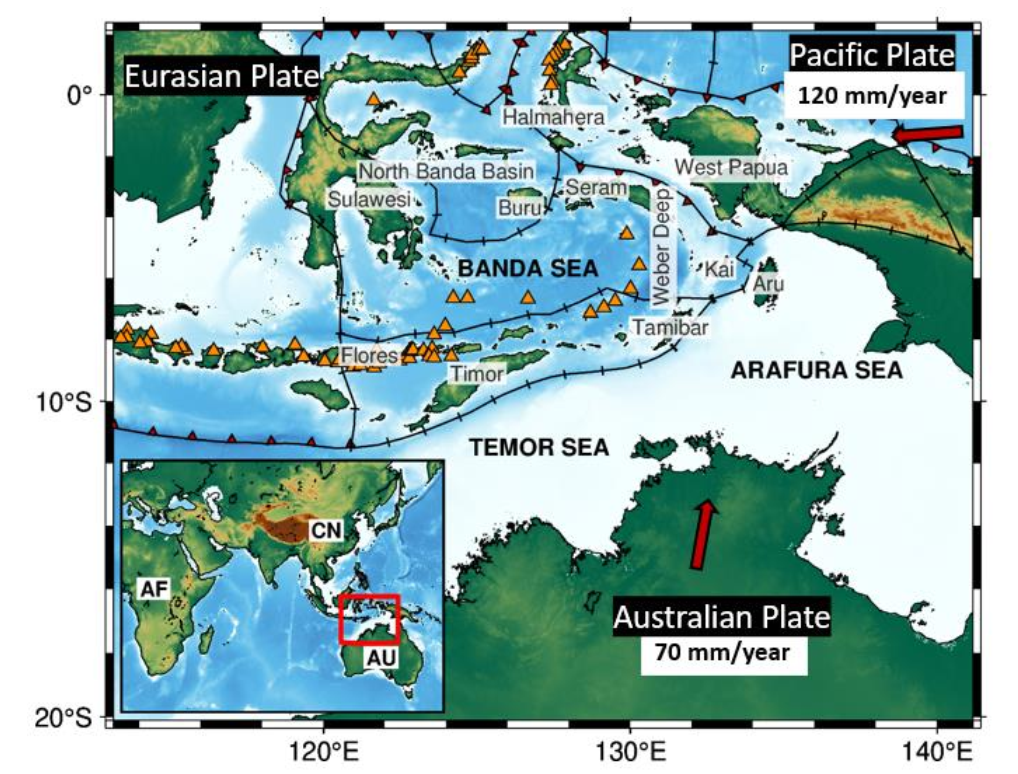

Earth System Physics

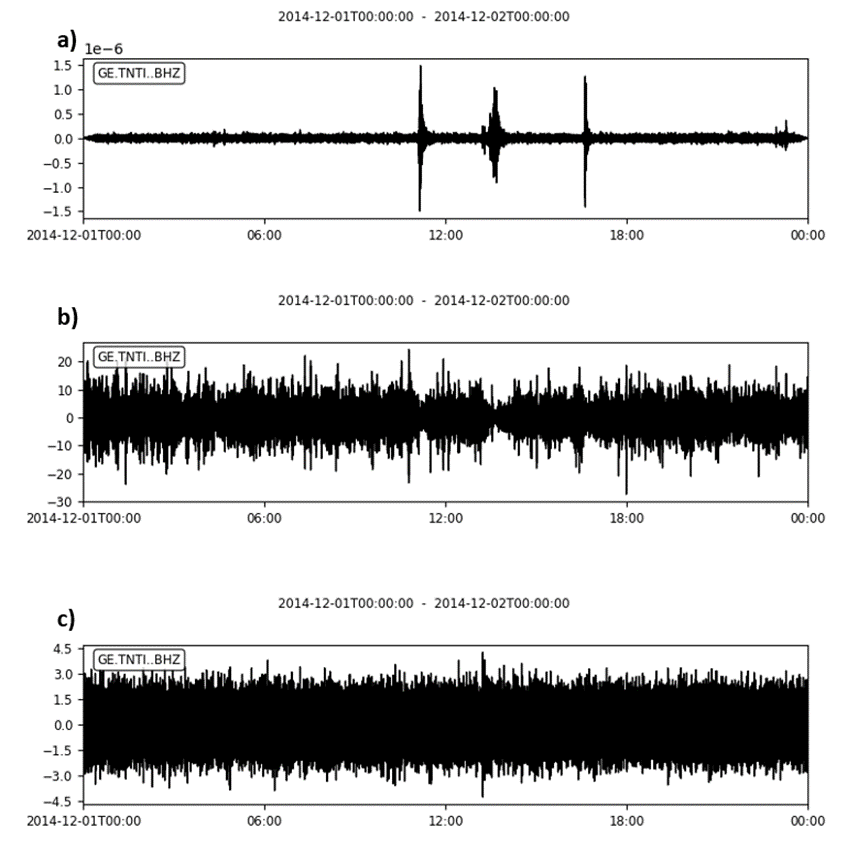

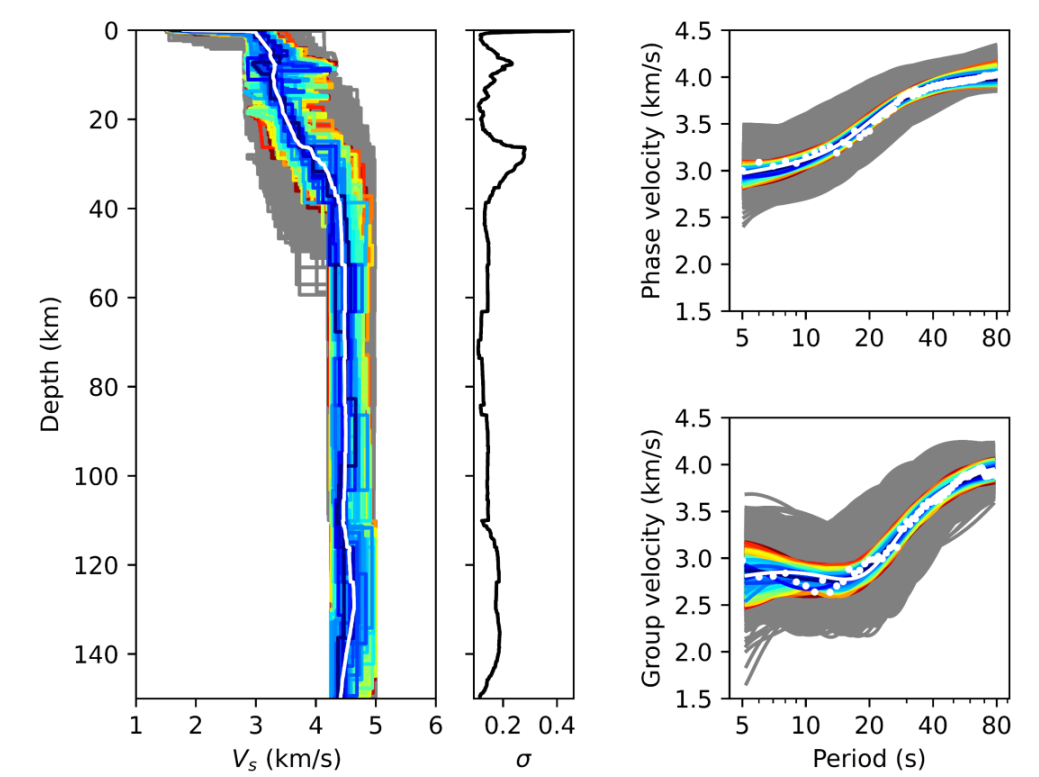

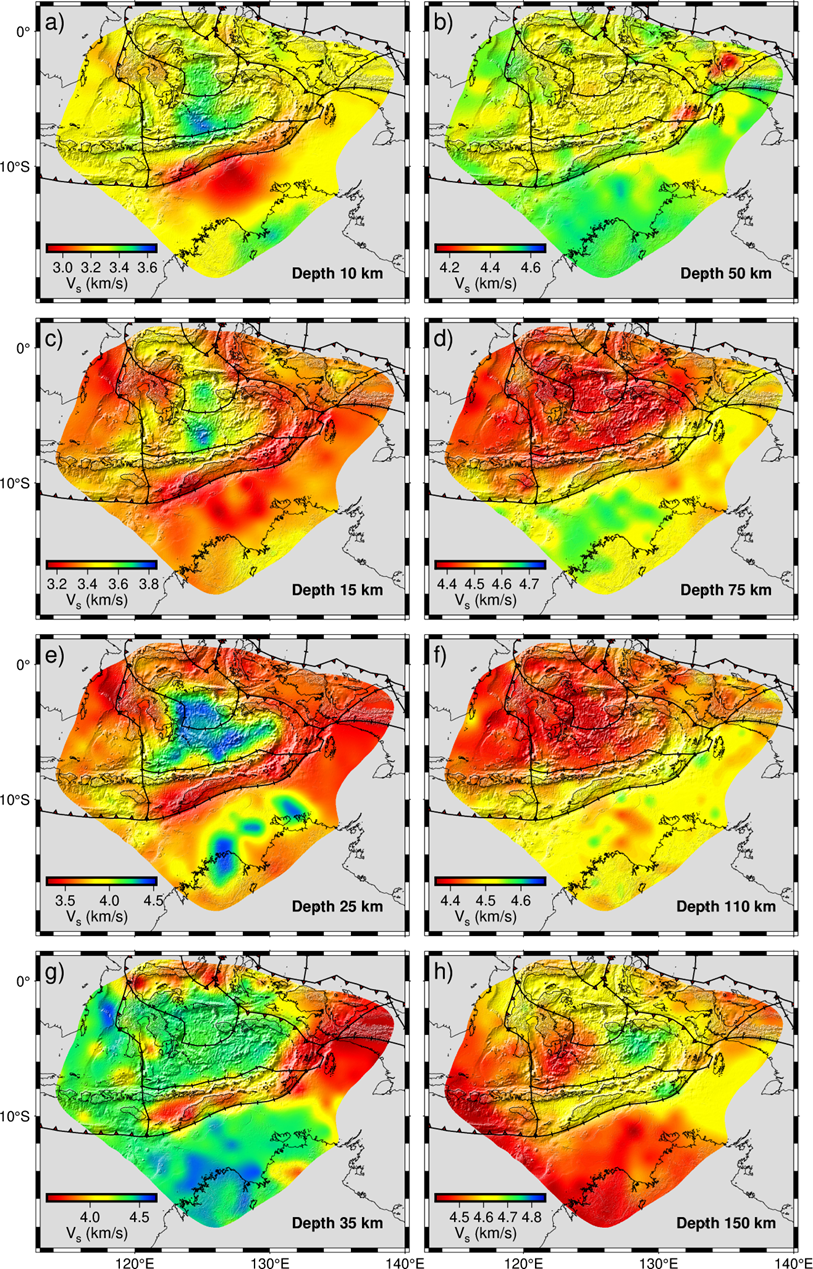

Ambient noise tomography (ANT) is an innovative geophysical technique that leverages the continuous background seismic noise generated by natural and human activities to image the Earth’s subsurface. Unlike traditional seismic methods that require active sources, such as explosions or controlled vibrations, ANT uses ambient noise, which is omnipresent due to phenomena like ocean waves, wind, and urban activities. This method involves deploying seismic sensors across a region of interest to record the ambient noise continuously over time, allowing for the extraction of valuable subsurface information without the need for disruptive active sources.

The process of ANT involves cross-correlating the recorded signals from pairs of seismic stations. Through this technique, the Green’s function, which represents the seismic wave’s impulse response between two stations, is extracted. Essentially, this gives a picture of how seismic waves would propagate through the Earth’s crust and upper mantle as if an earthquake had occurred at one station. These extracted signals are then used in tomographic inversion, a process that constructs a detailed velocity model of the subsurface. The resulting images can reveal various geological structures, such as fault zones, sedimentary basins, and volcanic features, providing insights into the region’s geological and tectonic framework.

ANT has broad applications, including studying the Earth’s crust and upper mantle, assessing earthquake hazards, and monitoring volcanic activity. Its advantages lie in its ability to provide continuous data collection, making it a cost-effective and non-invasive alternative to traditional seismic surveys. Additionally, because ANT uses ambient noise, it can be conducted in urban environments where other seismic methods might be impractical. This makes ANT an increasingly valuable tool for geoscientists seeking to understand subsurface structures and dynamics with minimal environmental impact.